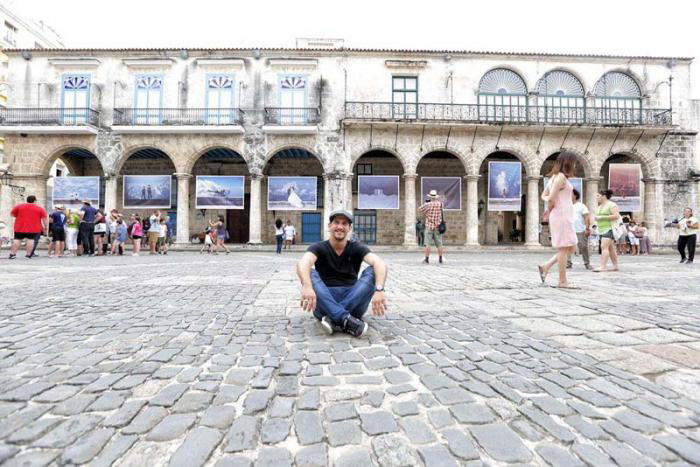

A Havana Malecón that doesn’t contain the sea, but is rather a cloud lookout point. The very city flooded in white steam…. That is what Gabriel Guerra Bianchini fantasizes, breaking “the damn circumstance,” “Make my wish come true of bringing us at least a horizon,” the photographer asks. “Allow me to fill this plaza with clouds; they are my utopia, the horizon and hope.” The clouds are the ones he has photographed for a long time; the plaza is that of Havana’s Cathedral Square, which in the 498 years the city celebrated on November 17 made its premier as an open-air gallery. Ten giantographies make up “…Es la esperanza”; for Bianchini, his “most desired personal exhibition.” The works, printed on canvas, take up the arches of the traditional Havana square. The creation process, Gabriel explains, is very simple. “It is the superimposition of two photos, two spaces. The clouds I have collected for years and spaces of my Havana with their characters.” He also tries to make “each cloud fit in, in the direction in which the light is shown as well as its tones.”

"...IT'S HOPE"

Why clouds? “In the midst of so much chaos,” says Gabriel, “drawing a focal point with the immensity is remembering how small we are, how insignificant this running around is, how simple are the things that really matter, and that calm that lives beyond.” The photographer of the bare elegance of Havana again resorts to the city as a stage. He breathes the art that is in the street and wants to be part of that movement. This time he is also pleased that it is “precisely one of Cuba’s most visited places.” He wants to bet on art being “at the reach of citizens, of the neighbors of the space they take up, of everybody. Without being closed in by any wall. That it can get wet with the rain, sleep outside and be an unexpected surprise for passersby.”

Based on true events, 1989 is set three years after the nuclear explosion in Chernobyl, when the first patients arrived in Havana to receive medical treatment for radiation-caused cancer. Malin is temporarily suspended from his position as a Russian Literature professor at the University of Havana, separated from his family, and sent to do a job that he does not feel prepared to do—work as a translator for Cuban doctors, the sick children and their mothers in hospitals across the city.

by Monica Rivero. Photo: Abel Rojas Barallobre